Nubian desert, March 2017, Credit: Hans Birger Nilsen, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Green Sahara

African sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) on grassland with white flowers. Credit: Aart Rietveld, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Did you know? The area that we call the Sahara is a huge desert that spans 11 countries in Africa. A long, long time ago, that whole area used to be an incredibly lush and green space that included grasslands, woodlands, and large lakes.

What time period?

From 10,000-15,000 years ago to 5,500 years ago

Why was the area habitable?

Heavy rains

Who lived in that space?

Animals, including humans, that typically inhabit savannah or grassland areas

Why did this occur?

African Humid Period

African Humid Period

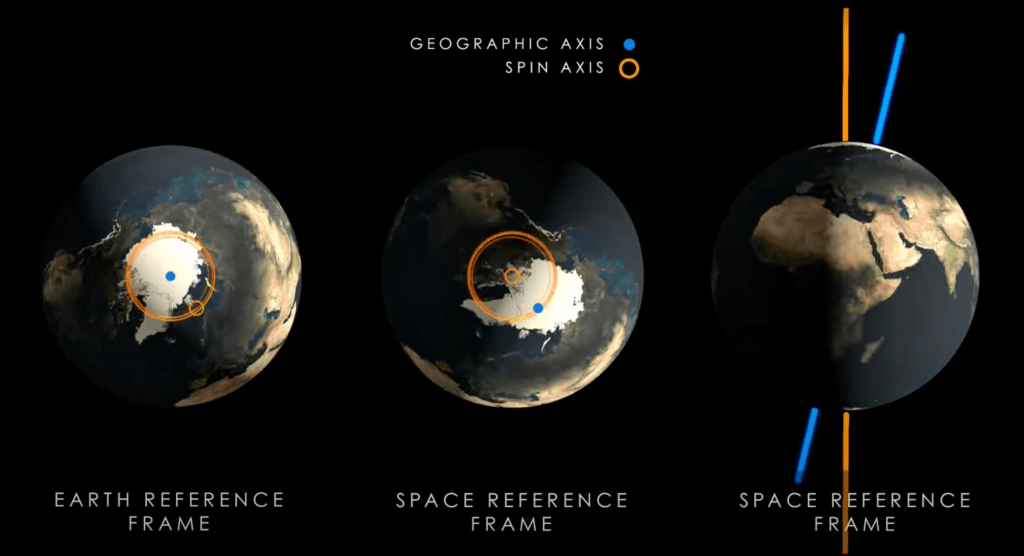

The spin axis that the Earth rotates around is shown in orange. The geographic north and south poles are shown in blue. When viewed from space, the geographic poles appear to “wobble” or spin away from the spin axis and then back again. Note: The size and speed of the spiral are greatly exaggerated for clarity. Video credit: NASA/GSFC Science Visualization Studio. Source with video: American Geophysical Union

The African Humid Period occurred because the Northern Hemisphere was closer to the sun than it is now. The area that we currently call the Sahara warmed. Moisture evaporated off the Atlantic Ocean, was drawn into northern and central Africa, and fell there as rain. Because of the rain, grasses, plants, and trees began to grow. The green and moist environment was a favorable living condition for humans and animals.

How did the northern hemisphere shift position?

In addition to rotating on an axis, the earth also wobbles

How long is the entire cycle of one wobble?

Approximately 40,000 years

How often does the wobble bring the north closer to the sun than the south?

Approximately every 26,000 years

How do we know that animals and humans lived in this area at that time?

Rock art and archaeology

Green Sahara Rock Art

Life-size rock carving of two giraffes located in Niger. Credit: Bradshaw Foundation

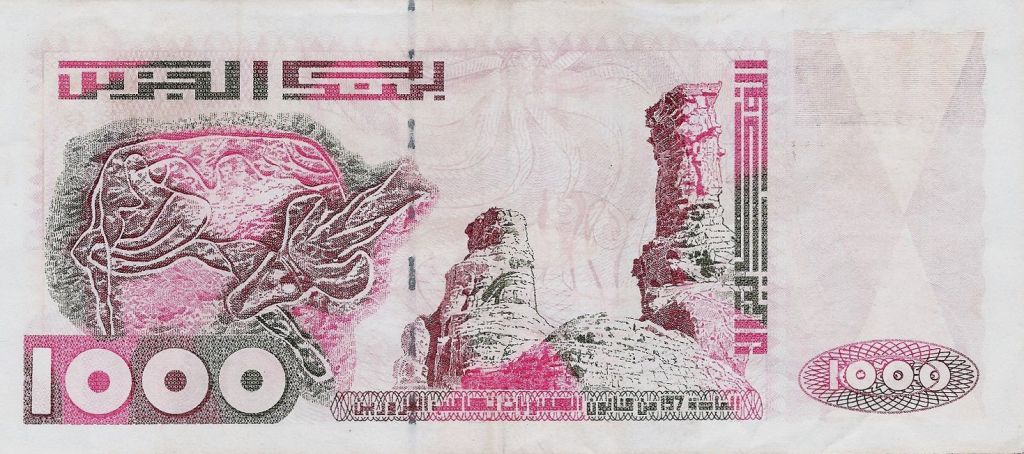

An Algerian banknote reproduces an ancient rock carving of an antelope or gazelle found at Tin Taghirt, Algeria. Credit: Trust for African Rock Art

Rock carving of an elephant located in Tadrart, Algeria. 2013, 2034.4685 © TARA/David Coulson. Credit: The British Museum

Carved image of a crocodile, Wadi Mathendous, Messak Settafet, Libya. 2013, 2034.3106 ©TARA/David Coulson. Credit: The British Museum

Carved image of cattle and two rhinos, Fourth Cataract region, Sudan. Credit: Stuart Tyson Smith, “Gift of the Nile?” In Across the Mediterranean – Along the Nile, Budapest: Institute of Archaeology and Museum of Fine Arts, fig. 4

Green Sahara Rock Art

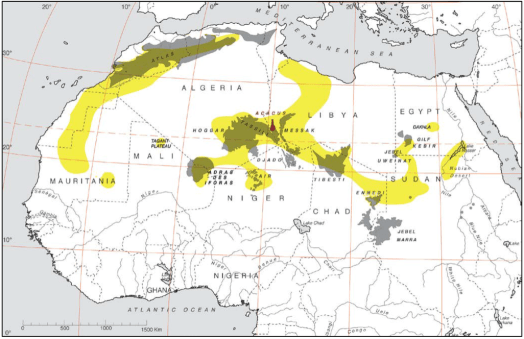

Map of the Sahara showing the main mountain systems (in grey) and the major rock art concentrations (in yellow). Credit: Marina Gallinaro, “Saharan Rock Art:Local Dynamics and Wider Perspectives,” Arts 2(4), 2013, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts2040350

Ancient humans who lived during the African Humid Period carved art into rocks across what is now called the Sahara. Their art depicts the animals they saw around them: animals that usually live in a savannah or wetland environment.

What animals are depicted in rock art of the Green Sahara?

Water buffalo, antelope, crocodiles, elephants, hippopotami, giraffes, and many others

What does the rock art tell us about humans?

The widespread nature of the art shows us how widespread human habitation was across the Green Sahara.

When is the rock art dated to?

Between 8,000 and 12,000 years ago

What other evidence is there from the Green Sahara?

Archaeological evidence of human communities

Green Sahara Archaeology

Harpoon heads, dating to 7,800 years ago, found at Gobero, a Kiffian-culture site located in what is now the Ténéré Desert, Niger. Credit: Paul Sereno

Archaeologists have excavated human settlements and human burials from the African Humid Period, showing that communities of people lived in what is now a dry desert environment.

What evidence of human habitation have archaeologists found?

Worked stone objects such as arrowhead, jewelry, harpoon heads, and fish hooks

What does the archaeological evidence tell us about humans?

The find spots show us where humans lived, the harpoon heads and fish hooks indicate that aquatic animals were found in the area, and the animal remains show what animals lived in that area.

What other evidence have archaeologists found?

Burial remains of humans and skeletal remains of animals that typically live in grasslands

What other archaeological evidence is there from the Green Sahara?

Pottery

Green Sahara Archaeology

Neolithic and Pre-Kerma pottery from Ginefab. (a) Calceiform beaker with stamped motif; (b) bowl rim with modeling and incised triangles; (c) ripple ware; (d) blacktopped red ripple ware and polished with milled rim (photos by Stuart Tyson Smith). Credit: Shayla Monroe, Stuart Tyson Smith, and Sarah B. McClure, “Pastoralism, hunting, and coexistence: Domesticated and wild bovids in Neolithic Sudan,” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 33(3), 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3223

Archaeologists have discovered Neolithic settlement sites, showing that humans lived at the Fourth and Third Cataracts of the Nile and in areas to the east and west of the river valley. For example, the site of Ginefab at the Fourth Cataract was occupied from the fifth to the third millennium (c. 5000–2000 BCE).

How do the Neolithic sites relate to later sites in the Nile Valley?

Many pottery types found at these Neolithic sites are also found at later predynastic Egyptian and Nubian Neolithic and A-Group sites.

How early are those Neolithic ceramics dated?

We first see these pottery types in the west and south of the Nile Valley in the sixth millennium (c. 6000–5000 BCE), and they only appear in the northern Nile Valley later, in the fourth millennium (c. 4000–3000 BCE, the predynastic or Badarian period).

What does that mean?

Humans were interacting with each other from at least as far south as the Sixth Cataract of the Nile (north of modern Khartoum, Sudan) to the southern part of modern Egypt, and many older traditions of pottery making moved from south to north.

What other evidence is there from the Green Sahara?

Lakes and megalakes!

Green Sahara Megalakes

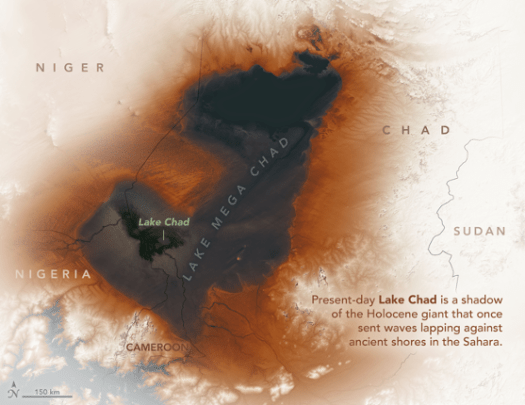

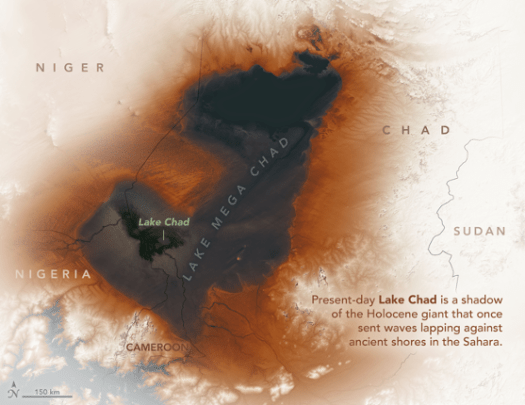

Reconstruction of Megalake Chad. Credit: Image created by Joshua Stevens from data gathered between 2000 and 2020 from the NASA Earth Observatory, SRTM, and Landsat data from the USGS. Source: Nasa Earth Observatory

Across what is today the Sahara, there is evidence of lakes and megalakes in modern Tunisia, Libya, Algeria, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Sudan.

What is a megalake?

A really big lake!

What is an example of a megalake?

During the African Humid Period, what is today Lake Chad was Megalake Chad, and it was much larger than the largest lake on earth today (the Caspian Sea), larger than all of the US Great Lakes combined, larger than the entire landmass of the United Kingdom.

Why are the ancient lakes important?

Water sources were necessary to support the human and animal life that is represented in rock art and found by archaeologists.

What was life like in the African Humid Period?

Mobile

Green Sahara Migrations

A comb from the Pan-Grave culture, found in southern modern Egypt and northern modern Sudan, dating to about 2000–1600 BCE, and a drawing of a proposed reconstruction by Rob Law, British Museum, EA 63762. Credit: Sally-Ann Ashton, 6,000 Years of African Combs, Cambridge: The Fitzwilliam Museum, 2013, fig. 13

Freshwater lakes hosted many types of marine life, and grassy and wooded lands were home to a variety of birds and mammals, including humans. During the African Humid Period, the area that is now the Sahara was rich in water and food sources. The warm, wet environment facilitated the movement of humans and animals across the land.

What are examples of the Green Sahara’s widespread culture?

Burial traditions, economies of cattle pastoralism and harvesting wild grain, and objects such as pottery, hair combs, stone maceheads, and stone palettes

What evidence of Green Sahara African cultures is found in the Nile Valley?

Toward the end of the Neolithic (c. 7000-6000 years ago), humans lived in seasonal camps along the Nile while herding, fishing, and gathering food. From burial items such as cosmetics, jewelry, combs, and palettes for grinding paint, we see that body decoration was widely practiced. Stone maceheads and pottery-making traditions first appear in the southern and later in the northern Nile Valley.

When does that culture end?

Archaeologists do not see a break or a rupture in the widespread culture of the Green Sahara and the time of the earliest rulers of the Nile Valley

So what does that mean?

Many cultural traditions of the predynastic period in the northern Nile Valley began in the southern Nile Valley or in areas to the east and west of the valley. The predynastic and early dynastic cultures of the ancient Nile Valley are firmly rooted in the cultural traditions of the Green Sahara. They are African cultures.

Green Sahara Migrations

Rain in Mombasa, Kenya, April 2009 (Nyali Beach Hotel). Credit: Andrew Thomas from Shrewsbury, UK, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Approximately 5,500 years ago, the environment slowly changed, and a drying out of many areas took place over a very long period of time. Even so, certain areas in the southern Nile Valley continued experiencing rains into the Badarian (c. 4400–4000 BCE) and Kerma Ancien (c. 2550–2050 BCE) periods or even later.

How long did it stay wet in the southern Nile Valley?

There were still prolonged periods of rain in what is today Sudan in the second millennium (c. 1000 BCE).

How long did it stay wet in the northern Nile Valley?

There were still prolonged periods of rain in the southern part of what is today Egypt in the mid-fourth millennium (c. 3500 BCE).

What are some occupation sites from this era?

Laqiya, Wadi Howar, Uweinat, and Gilf Kebir, just to name a few

So what does that mean for the people who lived there?

As parts of the environment slowly dried, people continued moving and interacting along the Nile River Valley and in the areas east and west of it.

The Green Sahara in Africa

Africa today (with parts of Europe and Asia also pictured), Credit: Google maps

So there was no break between the cultures of the Green Sahara and the cultures of the early Nile Valley rulers like Bull, Double Falcon, Scorpion, and Narmer?

Yes, that’s correct.

So what does that mean?

The Nile Valley cultures are firmly rooted in the cultures of the Green Sahara. They are all African cultures.

Where can I learn more about the African Humid Period and early Nile Valley cultures?

Read on!

Some Sources

African sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) on grassland with white flowers. Credit: Aart Rietveld, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Anselin, A. 2011. Some notes about an early African pool of cultures from which emerged the Egyptian civilisation. In Egypt in its African context: Proceedings of the conference held at The Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2–4 October 2009, K. Exell, ed., 43–53. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Arkell, A.J. and P.J. Ucko. 1965. Review of predynastic development in the Nile Valley. Current Anthropology 6 (2), 145–66.

Bárta. M. 2014. Prehistoric mind in context: An essay on possible roots of ancient Egyptian civilisation. In Paradigm found: Archaeological theory – present, past and future. Essays in honour of Evžen Neustupný, K. Kristiansen, L. Šmejda & J. Turek, eds., 188–201. Oxford: Oxbow Books

Bárta, M. 2010. Swimmers in the sand. On the Neolithic origins of ancient Egyptian mythology and symbolism. Prague, Dryada.

Červíček, P. 1998. Rock art and the ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Sahara 10, 110–11.

Drake, N.A., R.M. Blench, S.J. Armitage, C.S. Bristow, and K.H. White. 2010, Nov 22. Ancient watercourses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert. PNAS 108 (2), 458–62, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1012231108.

Egorova, Y. 2010. DNA evidence? The impact of genetic research on historical debates. BioSocieties 5 (3), 348–65, DOI: 10.1057/biosoc.2010.18.

Gallinaro, M. 2013. Saharan rock art: Local dynamics and wider perspectives, Arts 2(4), DOI: 10.3390/arts2040350.

Gatto, M., S. Hendrickx, S. Roma, and D. Zampetti. 2009. Rock art from West Bank Aswan and Wadi Abu Subeira. Archéo-Nil 19, 151–68.

Hassan, F.A. 1988. The predynastic of Egypt. Journal of World Prehistory 2(2), 135–85.

Henneberg, M., J. Piontek, and J. Strzałko. 1980. Biometrical analysis of the early Neolithic human mandible from Nabta Playa (western desert of Egypt). In Prehistory of the Eastern Sahara, F. Wendorf and R. Schild, eds., 389–92. New York: Academic Press.

Huyge, D. 2002. Cosmology, ideology and personal religious practice in ancient Egyptian rock art. In Egypt and Nubia: Gifts of the Desert, R. Friedman, ed., 192–206. London: British Museum Press.

Huyge, D. 2009. Rock art. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1).

Keita, Shomarka O.Y. 2021. Mass population migration vs. cultural diffusion in relationship to the spread of aspects of southern culture to northern Egypt during the latest predynastic: A bioanthropological approach. In Egypt at Its Origins 6, E.C. Köhler, N. Kuch, F. Junge, and A.-K. Jeske, eds., 323–38. Leuven: Peeters.

Kuper, R., ed. 2013. Wadi Sura: The cave of beasts. A rock art site in the Gilf Kebir (SW-Egypt). Cologne: Heinrich Barth Institut.

Kuper, R. and S. Kröpelin. 2006, Aug 11. Climate-controlled Holocene occupation in the Sahara: Motor of Africa’s evolution. Science 313 (5788), 803–7, DOI: 10.1126/science.1130989.

Makoni, M. 2021, Dec 10. The “Green Sahara” left behind fossil rivers. Eos 102, DOI: 10.1029/2021EO210654.

Monroe, S. S.T. Smith, and S.B. McClure. 2023, March 22. Pastoralism, hunting, and coexistence: Domesticated and wild bovids in Neolithic Sudan. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 33(3), 517–31, DOI: 10.1002/oa.3223.

Osborne, A.H., D. Vance, E.J. Rohling, N. Barton, M. Rogerson, and N. Fello. 2008, Oct 28. A humid corridor across the Sahara for the migration of early modern humans out of Africa 120,000 years ago. PNAS 105 (43), 16444–47, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0804472105

le Quellec, J.-l., P. de Flers, and P. de Flers. 2005. Du Sahara au Nil, peintures et gravures d’avant les pharaons. Paris: Collège de France.

le Quellec, J.-l. 2008. Can one “read” rock art? An Egyptian example. In Iconography without texts, P. Taylor, ed., 25–42. London, Warburg Institute.

Rowlands, M. 2007. The unity of Africa. In Ancient Egypt in Africa, D. O’Connor. and A. Reid, eds., 39–54. London: Taylor & Francis.

Schillaci, M.A., J.D. Irish, and C.C.E. Wood. 2009. Further analysis of the population history of ancient Egyptians. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 139, 235–43, DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.20976.

Sereno, P. 2023. The Gobero Story. Website hosted by University of Chicago.

El-Shenawy, M.I., K. Sang-Tae, H.P. Schwarcz, Y. Asmerom, and V.J. Polyak. 2018, May 15. Speleothem evidence for the greening of the Sahara and its implications for the early human dispersal out of sub-Saharan Africa. Quaternary Science Reviews 188, 67–76, DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.03.016.

Smith, S.T. 2018. Gift of the Nile? Climate change, the origins of Egyptian civilization and its interactions within northeast Africa. In Across the Mediterranean – Along the Nile, vol. I, T. Bacs, Á. Bollok, and T. Vida, eds., 325–46. Budapest: Institute of Archaeology and Museum of Fine Arts.

Wendorf, F. and R. Schild. 1998. Nabta Playa and its role in northeastern African prehistory. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 17, 97–123.

Wengrow, D. 2003. Landscapes of knowledge, idioms of power: The African foundations of Egyptian civilization reconsidered. In Ancient Egypt in Africa, D.A. O’Connor and A. Reid, eds., 121–35. London: UCL Press.

Wengrow, D., M. Dee, S. Foster, A. Stevenson, and C. Bronk Ramsey. 2014. Cultural convergence in the Neolithic of the Nile Valley: A prehistoric perspective on Egypt’s place in Africa. Antiquity 88, 95–111.

el-Yakhy, F. 1985. The Sahara and predynastic Egypt: An overview. Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 15 (3), 81–85.

Clearly it is inconceivable that communities throughout the entire length of the Nile Valley, a distance of c. 1800km, shared anything approaching a conscious social identity (e.g. of the sort that could be articulated in tribal or ethnic terms) during the fifth millennium BC. Instead, what came to be shared across this extensive region were the materials and practices—including, and perhaps especially, modes of ritual practice—out of which more local contrasts and group identities were constructed.

—Wengrow, Dee, Foster, Stevenson, and Bronk Ramsey (2014), p. 107

Last updated: 2 August 2023