Archaeological research tells of a long history of humans living in Nubia (the northern part of modern Sudan and southern part of modern Egypt). The area was inhabited during the time period we call the Green Sahara (from approx. 10,000–15,000 years ago to 5,500 years ago). And people continued living there during subsequent periods of environmental change. As some parts of the land east and west of the Nile River gradually dried out, people continued to live in oases and continued to travel through the deserts and via waterways to reach people and places elsewhere in Africa.

New models of understanding cultural interactions: An array of cultures

Older publications tended to draw sharp distinctions between the ancient cultures of Egypt and Nubia. That practice is now being overturned. So too is the overly simplistic and mistaken idea that one so-called Egyptian culture existed in the north and one so-called Nubian culture existed in the south. Instead, scholars increasingly recognize that different groups of people were migrating into and out of the Nile River Valley during the time of the Green Sahara, during the predynastic period, and later throughout the pharaonic period. The resulting mix of people and the complex blendings of cultural traditions meant that a variety of people and cultures shared the same space.

New models of understanding cultural interactions: Entanglement

Increasingly, scholars are turning their attention to innovations in cultural traditions that resulted from the movement of people and ideas in the Nile Valley. When local and non-local people came into contact with one another, entanglements resulted: cultural traditions were shared, objects were reinterpreted and given different meanings, practices changed, and offspring physically reflected new genetic admixtures. These entanglements are reflected in the archaeological record in creative and unique customs that are neither the original local nor the original non-local, but instead are new practices that show the fluidity and flexibility of human cultures when they are open to change.

New models of understanding cultural interactions: Dynasty 25 kings

Another outdated Egyptological theory that is no longer accepted is the mistaken idea that the Dynasty 25 kings of Kush were foreign invaders of the northern Nile Valley (modern Egypt). Archaeological evidence clearly shows that social, cultural, and diplomatic relations between the northern and southern Nile Valley continued under the Dynasty 25 kings as they had for centuries. Kushite dominion extended over what is today Egypt through an alliance between the two centers of worship of the deity Amun: the city of Thebes in the north (modern Egypt) and the city of Napata in the south (modern Sudan).

Gold ring with a bezel depicting Amun of Thebes in the center and Amun of Napata on either side. Amun of Thebes is the human-headed figure wearing a double-plumed crown and sun disk. Amun of Napata are the ram-headed figures wearing a double-plumed crown and sun disk resting on a set of horns. 110–50 BCE. From Pyramid N 20 at Meroë, modern Sudan. Credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 24.569

Nubia during pharaonic history

Nubia was inhabited throughout antiquity by population groups who were named by archaeologists and historians (e.g., Pre-Kerma, A-Group). Most of those groups of people did not leave written records, so we do not know what languages they spoke, and we do not have their records of their lives and histories. Their material cultures are known from domestic spaces and burial sites.

Nubian people played various roles throughout pharaonic history, in the way that every human population reflects various types of expertise. Textual and material remains show them to be skilled as archers, gold workers, and leather workers, builders of monumental structures, and makers of fine ceramics, sculptures, and carvings. The many cultures of the northern and southern Nile Valley (modern Egypt, Nubia, and Sudan) interacted with one another via work and marriage, in trade, diplomatic relations, and war. When people from different regions came in contact with one another, they shared their ideas and their cultures, resulting in new cultural expressions that reflected their interactions.

Large scarab found at Tombos, Nubia. The image of the two offering bearers reflects a new artistic tradition that is influenced by but does not simply copy the artistic tradition of the northern Nile Valley. Credit: Buzon and Smith, 2023, fig. 12

The Dynasty 25 kings of Kush

The kings of Kush are called Dynasty 25 when they are referred to in reference to their rule over modern Egypt, c. 747–656 BCE. Their reigns, and Nubian rulership in general, are marked by the prominent role given to royal women, for example, in the important religious-political role of the God’s Wife of Amun. The king’s daughter occupied that role in the ancient city of Thebes (now Luxor, in modern Egypt). The position existed prior to Dynasty 25, but with the reign of Dynasty 25 kings, the status of the role was greatly enhanced. The power of the God’s Wife of Amun is represented by her names that are written inside a cartouche, like the king’s names, and in her royal titles. In Nubia, Meroitic ruling queens are depicted on temples alongside queen-mothers, making offerings with the ruling king and conquering their enemies.

Royal representations

In monumental art in the northern Nile Valley (modern Egypt), the Dynasty 25 kings wrote about themselves using that region’s ancient language and its hieroglyphic writing system. They represented themselves on temples there in a variety of ways, in some cases using traditional artistic standards of the northern Nile Valley and in other cases using a Kushite style. In Nubia, those same kings depicted themselves in ways that combined iconography from the north with the Kushite royal style. Most royal texts from that era suggest bilingualism among the Kushite elite. For example, texts are often written in the ancient Egyptian language, but personal names remain Kushite and are not “Egyptianized.”

Elements of royal iconography that appear in art during Dynasty 25 include a headdress, called the Kushite cap, two rearing cobras on the king’s head rather than the more usual single uraeus, and distinctively Kushite jewelry, for example, ram-head earrings and pendants featuring rams, which was the form of the deity Amun in Nubia. The Kushite kings combined those distinctive cultural markers with bodily postures derived from Old Kingdom royal statuary, creating an artistic style clearly rooted in ancient traditions but with original elements unique to their time period.

Top of a bronze statuette of a Kushite king of Dynasty 25 wearing the Kushite cap with single uraeus. Credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 72.4433

Method of rule

From the end of Dynasty 20 through Dynasty 24, the time period that modern historians call the Third Intermediate Period, ruling authority was dispersed among multiple kings and priests who had power bases at various sites in the northern Nile Valley (modern Egypt). In the mid-8th century BCE, the Kushite King Piankhi (sometimes called Piye) traveled from the south going north. At site after site, he subjugated the local rulers of the northern Nile Valley to his authority.

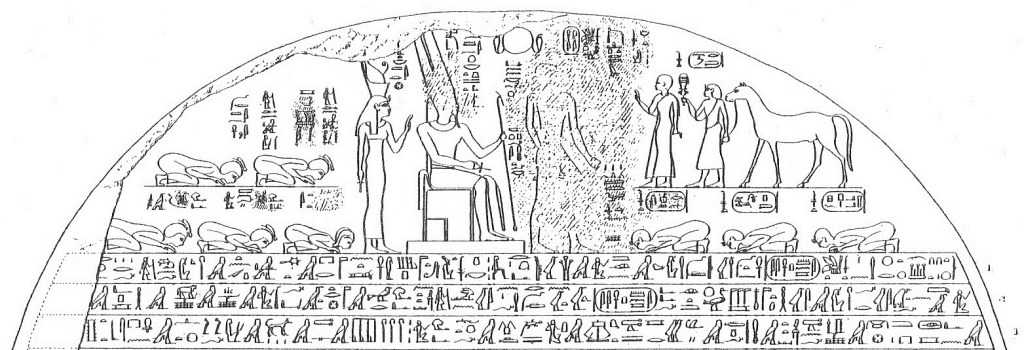

A stela found at Jebel Barkal (in modern Sudan) records those events and depicts rulers who surrendered to Piankhi and accepted his supremacy. One of the local rulers prostrating himself before Piankhi on the stela is Iuput II. His name and the names of the other defeated rulers are written in cartouches, showing that King Piankhi extended his rule over those other kings.

Iuput II is depicted on another stela, this time alone, again with his name in a cartouche. On that stela, the figure of Iuput II combines elements of art from the northern and southern Nile Valley (modern Egypt and modern Sudan). His body posture is commonly found in art of the northern Nile Valley (modern Egypt). And his facial features and manner of dress follow royal depictions from Kush (modern Sudan). The combination of art styles from the northern and southern Nile Valley shows the interconnectedness of cultural expression among these ancient cultures in Africa.

Stela of King Iuput II. Credit: Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 59.17

The fact that Iuput II is depicted on this stela with royal symbols like the bull’s tail, uraeus, and name in a cartouche shows that Piankhi allowed conquered rulers to continue to exercise authority at a local level. But that model of rule is not typical of pharaonic kingship. The Kushite King Piankhi introduced this innovative type of administration.

As the preeminent rulers, the Dynasty 25 Kushite kings restored temples that had fallen into disrepair and enhanced existing temples by adding new features, like kiosks and pylons. Temple repair and rebuilding had long been a traditional role of rulers of the northern Nile Valley. So according to that age-old understanding of rulers’ roles and responsibilities, these Kushite kings were carrying out the customary work of rulers. The Dynasty 25 kings also reestablished trade and diplomatic relations between the Nile Valley and western Asia. Those networks had lapsed during the Third Intermediate Period. With the rule of the Kushite kings, the so-called Third Intermediate Period ended.

The last intact column of what had originally been ten columns built by the Dynasty 25 king Taharqa (690–664 BCE) in the first court of Karnak temple, Luxor. This area of Karnak temple is called the kiosk of Taharqa. Also located there was a stone shrine that he built, probably for the bark (boat) of the deity Amun. Credit: Rabax63

Below are a few highlights of Nubian history from the time before Dynasty 25 came into power.

Qustul

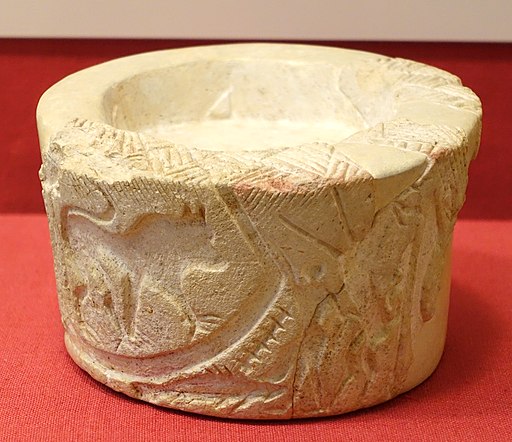

A famous early piece of evidence of material culture from Nubia is the Qustul incense burner. The stone bowl-like burner is decorated with a Horus falcon, a rosette, and a figure wearing the hedjet (white) crown. In later times in the northern Nile Valley (modern Egypt), those items are associated with royal symbolism. Other images on the incense burner also found on later artifacts throughout the Nile Valley include the false door and boats. This burner is one piece in the growing body of evidence that shows that cultural traits were shared across the First Cataract, which was commonly seen as a border between ancient Egypt and ancient Nubia.

Qustul incense burner, found in a tomb in Lower Nubia, now in the ISAC Museum (formerly: Oriental Institute Museum), University of Chicago. Credit: Daderot

The Qustul incense burner has been dated to the early 4th millennium BCE, long before the start of pharaonic history. The reign of Narmer in the late 4th millennium BCE (c. 3100 BCE) is typically identified as the beginning of pharaonic history. This means that images found in the northern Nile Valley (modern Egypt) during the pharaonic era are encountered before the pharaonic era in the southern Nile Valley (Nubia, or the northern part of modern Sudan and the southern part of modern Egypt). Even earlier than the Qustul incense burner is the evidence from Nabta Playa, a site where humans gathered seasonally. Their dwellings, burial places, and large stone structures demonstrate human culture and organization at a very early date.

Nabta Playa

Nabta Playa is a site in Nubia located nearly at the modern border between Egypt and Sudan, to the west of the modern artificial reservoir Lake Nasser. Human activity at the site dates to as early as 10,000 years ago, during the Neolithic period. At that time, the area was mostly grassland, home to many species of large mammals, and a lake at the site provided abundant water.

In the Neolithic era, northern Nubia was populated by cattle pastoralist societies that relied on lakes (playas) and grasslands for their cattle and for themselves. As the climate across Africa changed, these African societies migrated and seem to have settled in the Nile Valley at sites like Qustul and Naqada. These Nubian cultures are the forerunners of what we now refer to as the ancient cultures of modern Egypt and modern Sudan.

The people of Nabta Playa

The African people who used the site of Nabta Playa left traces of their occupation in their domestic spaces, for example, the ceramics they used and the different types of food they ate. They were nomadic people, who used the site only at certain times of the year. They kept sheep and goats, and later, they kept cattle, perhaps as signs of wealth and power, as found among later pastoralists in Africa, and still today.

Evidence from around 6100 BCE suggests that the site came to be used as a social and ceremonial center. People from around the area seem to have gathered there for ceremonies that may have affirmed a shared identity or celebrated a shared occasion. The event involved the sacrifice of a large amount of cattle, as suggested by the many cattle bones found in one area of the site.

The African people who periodically used Nabta Playa also quarried, shaped, and hauled to the site large stones, up to nine feet tall, and smaller stones, then arranged them into complex structures. Thirty structures in total have been identified, including one in a circle. The circular arrangement of stones may have been a way of tracking time, like a calendar, or tied to the solstice and constellations in the night sky. Analyses of silt that the stones stood in and radiocarbon dates from the quarry indicate that the stone structures were set up between 4600 and 3400 BCE.

Reconstruction of the stone circle at Nabta Playa, on display at the Nubian Museum in Egypt. Credit: Raymbetz

Also erected at the site were stones that served to commemorate people who had died. Archaeological analysis of the people buried at Nabta Playa show that they were healthy in life. Their grave goods show their participation in an exchange of goods and ideas with people who lived far away, in the Nile Valley, in areas farther south in Africa, and in the Sinai peninsula.

A note on modern construction of history

The historical divisions (Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms; First, Second, and Third Intermediate Periods; Late Period) are modern designations applied to ancient history. Although some earlier history books included Dynasty 25 in the Third Intermediate Period, that view has lost credibility. The modern label “Third Intermediate Period” suggests that the rulers of that era are outside of the “norm” or are not true rulers in comparison with kings of the New Kingdom or Late Period. As the text above shows, the Dynasty 25 rulers saw themselves as renewing pharaonic kingship. Their depictions reflect their unique artistic style and a traditional style of earlier pharaonic eras, and they enhanced and refurbished many temples in what is today Egypt. In addition, the way that modern historians have configured the so-called Intermediate Periods, they end with the unification of the northern Nile Valley (modern Egypt) under a conquering ruler. Piankhi’s conquest of the north resulted in unification. As a result, Dynasty 25 is now recognized as part of the Late Period.

Sources

Ashby, S. 2018. Dancing for Hathor: Nubian women in Egyptian cultic life. Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies, 5. http://dx.doi.org/10.5070/D65110046

Ashby, S. 2020. Calling out to Isis: The enduring Nubian presence at Philae. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias.

Ayad, M.F. 2009. God’s wife, God’s servant: The god’s wife of Amun (740–525 BC). New York: Routledge.

Buzon, M. 2011. Nubian identity in the Bronze Age: Patterns of cultural and biological variation. Bioarchaeology of the Near East 5, 19–40.

Buzon, M.R. and J. Marshall. 2022. Countering the racist scholarship of morphological research in Nubia: Centering the “people” in the past and present. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35, 2–18.

Buzon, M.R. and S.T. Smith. 2023. Tumuli at Tombos: Innovation, tradition, and variability in Nubia during the early Napatan period. African Archaeological Review 40, 621–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-023-09524-x.

Cooper, J. 2018. Kushites expressing “Egyptian” kingship: Nubian dynasties in hieroglyphic texts and a phantom Kushite king. Agypten und Levante 28, 143–67.

Ehret, C. 2023. Ancient Africa: A global history to 300 CE. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Faraji, S. 2022. Rediscovering the links between the earthen pyramids of West Africa and ancient Nubia: Restoring William Leo Hansberry’s vision of ancient Kush and Sudanic Africa. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35, 49–67.

Frankfort, H. 1948. Kingship and the gods, a study of ancient Near Eastern religion as the integration of society and nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gatto, M.C. 2011. The Nubian pastoral culture as link between Egypt and Africa: A view from the archaeological record. In Egypt in its African Context, K. Exell, ed., 21–29. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Gatto, M.C. 2014. Cultural entanglement at the dawn of the Egyptian history: A view from the Nile First Cataract region. Origini 36, 93–123.

Heard, D.D. 2022. The barbarians at the gate: The early historiographic battle to define the role of Kush in world history. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35, 68–92.

Keita, S.O.Y. 2021. Mass population migration vs. cultural diffusion in relationship to the spread of aspects of southern culture to northern Egypt during the latest predynastic: A bioanthropological approach. In Egypt at Its Origins 6, E.C. Köhler, N. Kuch, F. Junge, and A.-K. Jeske, eds, 323–38. Leuven: Peeters.

Keita, S.O.Y. 2022. Ideas about “race” in Nile Valley histories: A consideration of “racial” paradigms in recent presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from “Black Pharaohs” to mummy genomes. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35, 93–127.

Lemos, R. 2023. Can we decolonize the ancient past? Bridging postcolonial and decolonial theory in Sudanese and Nubian archaeology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 33, 19–37. doi:10.1017/S0959774322000178

McKim Malville, J. 2015. Astronomy at Nabta Playa, Southern Egypt. In Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, C. Ruggles, ed., 1079–90. New York: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_101

McKim Malville, J., R. Schild, F. Wendorf, and R. Brenmer. 2007. Astronomy of Nabta Playa. African Skies/Cieux Africains 11, 2–7.

Minor, E. 2018. Decolonizing Reisner: The case study of a Classic Kerma female burial for reinterpreting early Nubian archaeological collections through digital archival resources. In Nubian archaeology in the XXIst century: Proceedings of the thirteenth international conference for Nubian studies, Neuchâtel, 1st-6th September 2014, M. Honegger, ed., 251–62. Leuven: Peeters.

Näser, C. 2000. Structures and realities of Egyptian-Nubian interactions from the Late Old Kingdom to the early new Kingdom. In The First Cataract of the Nile: One Region – Diverse Perspectives, D. Raue, S.J. Seidlmayer, and P. Speiser, eds, 135–48. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Rice, M. 2003. Egypt’s making: The origins of ancient Egypt 5000-2000 BC. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Russman, E. 1989. Egyptian sculpture: Cairo and Luxor. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Smith, S.T. 1998. Nubia and Egypt: Interaction, acculturation, and secondary state formation from the third to first millennium B.C. In Studies in culture contact, J. Cusick, ed., 256–87. Southern Illinois University: Center of Archaeological Investigations.

Smith, S.T. 2003. Wretched Kush: Ethnic identities and boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian empire. New York: Routledge.

Smith, S.T. 2018. Gift of the Nile? Climate change, the origins of Egyptian civilization and its interactions within northeast Africa. In Across the Mediterranean – along the Nile, vol. I, T. Bacs, Á. Bollok, and T. Vida, eds, 325–46. Budapest: Institute of Archaeology and Museum of Fine Arts.

Smith, S.T. 2022. “Backwater Puritans?” Racism, Egyptological stereotypes, and cosmopolitan society at Kushite Tombos. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35, 190–217.

Smith, S.T. 2023. Out of the shadow of the texts: Reinvigorating archaeology’s role in ancient Nubia and modern Egyptology through a borderlands perspective. In From households to empires. Papers in memory of Bradley J. Parker, J.R. Kennedy and P. Mullins, eds, 149–67. Leiden: Sidestone Press, https://doi.org/10.59641/d38e92c5

Smith, S.T. and M.R. Buzon. 2014. Colonial entanglements: “Egyptianization” in Egypt’s Nubian empire and the Nubian dynasty. In Proceedings of the 12th international conference for Nubian studies, 01.–06. August 2010, D. Welsby and J. Anderson, eds, 431–42. London: British Museum Press.

Smith, S.T. and M.R. Buzon. 2018. Cross-cultural interaction in the ancient Egyptian and Nubian borderland. In Modeling cross-cultural interaction in ancient borderlands, U.M. Green and K.E. Costion, eds, 89–113. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813056883.003.0005

Spencer, N., A. Stevens, and M. Binder. 2014. Amara West, Living in Egyptian Nubia. London: The British Museum.

Török, L. 1997. The kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic civilization. Leiden: Brill.

Török, L. 2002. The image of the ordered world in ancient Nubian art: The construction of the Kushite mind (800 BC–300 AD). Leiden: Brill.

Wasylikowa, K. and J. Dahlberg. 1999. Sorghum in the economy of the early Neolithic nomadic tribes at Nabta Playa, southern Egypt. In The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa, M. van der Veen, ed., 11–31. Boston: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-6730-8_2

Wendorf, F. and R. Schild. 1998. Nabta Playa and its role in northeastern African prehistory. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 17, 97–123.

Wendorf, F. and R. Schild. 2001. Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, volume 1: The archaeology of Nabta Playa. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0653-9.

Williams, B. 1999. Kushite origins and the cultures of northeastern Africa. In Studien zum antiken Sudan: Akten der 7. Internationalen Tagung für meroitische Forschungen vom 14. bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/bei Berlin, S. Wenig, ed. 372–92. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Yahky-el, F. 1985. The Sahara and predynastic Egypt: An overview. Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 15,3, 81–85.

Yurco, F. 1996. The origin and development of ancient Nile valley writing. In Egypt in Africa, T. Celenko, ed., 34–37. Indianapolis, IN: Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Last updated: 6 October 2024